By Bailey Kestner

Randy Hester, former landscape architect and professor at the University of California, Berkeley, is this year’s Garvan Chair and visiting professor in landscape architecture for the Fay Jones School of Architecture. In this role, he has traveled to Fayetteville several times throughout the fall semester to participate in studio sessions and design critiques with students and faculty members. On Sept. 22, he joined landscape architecture students and their professor on Mount Kessler in southwest Fayetteville.

“It’s unusual for a city to have that kind of natural resource so close to where everyone is living,” Hester said. “The mountain seems like the old and wild Arkansas, but is actually only 10 to 15 minutes away from campus.”

Mount Kessler is privately owned, but it has had some threats to parts of it for subdivision for housing. The Fayetteville community, however, has been assertive in wanting to preserve Mount Kessler as a place where people can go to experience nature, as well as a resource for ecological study.

Hester said that he thinks this is why the Fayetteville City Council felt that it was important enough to spend public money to buy some of the property so that it wouldn’t be bought by others.

Landscape architecture students are participating in a vertical studio, which combines together students from second- through fifth-year levels. Led by professors Carl Smith, Kimball Erdman and Noah Billig, the students are completing two projects this semester that focus on the environment and experience of Mount Kessler.

“The projects are focused on what the really unique things about Mount Kessler are,” Hester said. “The rock foundations are extraordinary to an outsider; it has an incredible landscape.”

During that September hike, the students first were told to find places on the mountain that spoke to them. They began the project by focusing on the experiences that people have there.

“I wanted to see what made them go, ‘wow,’” Hester said. “Or perhaps what they thought was creepy, or where was the perfect place to lie down and just look at the leaves.”

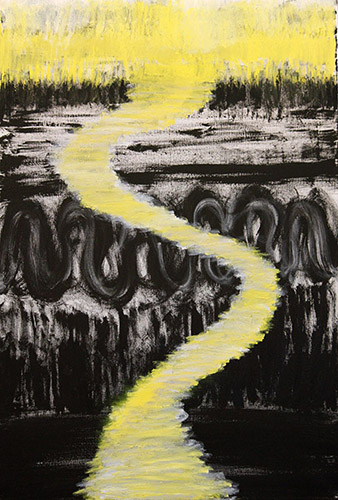

In the first project, the students recorded these emotional responses they experienced from being immersed in the landscape. Hester said there is a progressing field of study related to architecture and landscape architecture, known as the phenomenal logical response. The phenomenal logical response is partly traditional science and partly mystical science.

“We know we have some relationship with nature that can partly be explained by science,” Hester said. “But then, some part of it is primal.”

Phenomenologists study the experience of space in design fields. For instance, rather than just thinking about architecture as making a beautiful set of technology, they also ask, “But how does this design make me cry?”

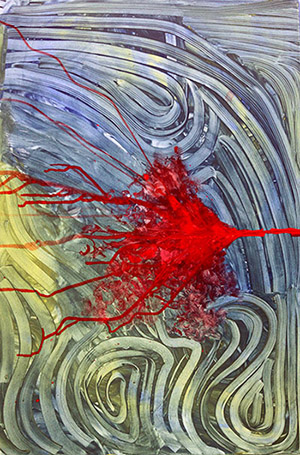

To start analyzing how Mount Kessler arouses emotion, students were assigned to build something on the mountain, using materials they found in the landscape. They were to create something that would heighten others’ experiences of the places they themselves experienced there. One student used red berries to create a design in the cracks of an old, decaying tree.

“Normally you would just pass by,” Hester said. “Just with the ‘little invention,’ a person’s experience can be completely heightened.”

This activity led to the second part of the studio project, which concerned the character for the mountain as a whole, as well as where different experiences are found.

“Students first mapped the soils,” Hester said. “Then added another map of geology, then hydrology, then vegetation, then wildlife. They overlapped each on top of the other with transparencies.”

The students looked for the patterns that were made by layering the sections on top of each other. The overlay became much more about the phenomenal experience, and the mapping together of the layers determined the character of the area.

“It’s sort of a combination of the natural science of soils and such with things that are usually slightly out of our range of understanding,” Hester said. “Like our relationship with nature, creation and faith that really make up our experiences.”

The outcome of the activity was finding the ecological character, the experience character, and the activity character of Mount Kessler. The answers to these questions allowed students to find which lands are most important for the city to purchase next, or which ones to preserve in some ways.

Hester said he focused on teaching the students that landscape architecture is about designing something really small, like a garden, versus something large, like Northwest Arkansas. He explained that while we dwell in a small space, we are dependent upon the whole region.

When asked what he felt he is teaching the students, Hester said it was much easier to answer, “How are the students teaching me?”

“I’m learning far more than I’m teaching them,” Hester said.

Hester, from North Carolina, doesn’t know the landscape of Northwest Arkansas, as well as the studio students who currently live here. Though the climate and plants are similar, Hester said he has had to ask the students many questions.

“They learn by having to explain things to me,” he said. “In some ways, it’s like a test for them without them even realizing it. By me asking them questions about the area, it makes them think about the area differently.”

Hester said he thinks that the range of ages and experience levels of the landscape architecture students in the studio has benefitted all of them.

“It’s interesting,” Hester said. “The older students always believe they know more, but the sophomores will often make good insights.”

The range of year levels working together also prepares the students for their future careers. The students almost always work in teams, which is very similar to the profession of an architect.

“You have to work with people who don’t speak the same language as you, or maybe people you don’t like,” Hester said. “It’s collaborative design, the exchanging of information between different people.”

Hester, who was invited to be part of the school’s lecture series last year, said he knew he wanted to come back. At a conference in March, Hester approached Mark Boyer, head of the Department of Landscape Architecture, and asked him, “So when are you going to invite me back?” – without even knowing the school had a visiting professor position. Boyer invited Hester as the Garvan Chair, which is funded by a financial gift from the late Verna Cook Garvan, the benefactress of Garvan Woodland Gardens.

“The students here are really extraordinary. They’re completely appealing to me,” Hester said.

One student in particular, Zach Foster, a fifth-year landscape architecture student, inspired Hester. One afternoon, Hester was able to talk to Foster about his plans post-graduation.

“He’s a very interesting young man,” Hester said. “I expect him to be the next governor of the state.”

Hester said he has been able to get to know the studio students better in the few times he’s spent time with them than with students he has taught for full semesters at Berkeley College.

“These students work hard and are genuine people,” he said. “No fakery, which is often the case with college students. I’ll follow some of these students and want to know where they’re working in the future – I’ll expect them to be in touch with me the rest of my life.”

The studio faculty members Hester is teaching with have inspired him as well. He said that they really have made the class happen, and that he merely drops in along the way. The way the professors structured the class allowed him to easily get to know the students, the project and the landscape.

“Kimball Erdman, Noah Billig and Carl Smith did an incredible job at integrating the visiting professor,” Hester said. “Now all I’m doing is waiting for them to invite me back again.”