By Michelle Parks

CriticalMass started in 2002 as an invited forum where graduate students could share their thesis project work with other graduate schools of architecture in the Southeast Region of schools accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board. Each year, select students receive critiques and advice from design professionals who serve as distinguished guests.

In early April, fifth-year architecture student Brady Duncan traveled to the University of North Carolina campus in Charlotte – as the only undergraduate student to attend this year’s CriticalMass. Despite the fact that he was one of 12 students invited to participate, the atmosphere felt open and inviting rather than exclusive.

In fact, while in Charlotte, he made fast friends with some of the UNC graduate students, who showed him the city after the official business was done. Some other students showed interest in his work. They were from the University of Virginia, where he’s considering going to graduate school after he finishes his studies at the U of A in December. Eventually, Duncan said, he wants to teach architecture at a university.

During the day of presentations at CriticalMass, students were scheduled in 30-minute slots, with only five minutes of that allotted for each student to describe their project. The remaining time was given for critique and conversation with Brian Johnsen and Sebastian Schmaling, co-founders of Johnsen Schmaling Architects, who were this year’s distinguished guests. Duncan recorded that discussion and made notes as he played it back.

Duncan’s project, “Memoria Technica,” involves the design for a museum for hardwood products manufactured in the Fort Smith region, in a studio taught in the spring semester by Greg Herman, associate professor. Herman and professor Marlon Blackwell suggested that Duncan attend CriticalMass. Duncan’s studio work for this project includes hand drawing, digital work and his process illustrated – a combination not common among the schools represented.

Duncan, a native of Little Rock, said he signed up for Herman’s studio because he wanted something different. He’d tackled urban projects in several previous studios, and he’d just finished the fourth-year comprehensive studio. For that studio in particular, he felt he worked at a breakneck speed, focused more on production than process and iterations.

Duncan approached the museum design as a story of the place. On an early visit to the site in Fort Chaffee, his attention was drawn to one of the last old-growth trees there. It was burly and knotted and strange. He imagined a fictitious history about the last tree, and the museum serving as a sort of shrine to it.

For this project, he thought about how this building differs from others, in its particular need to display artifacts. But he also considered how it differs from an art museum. And just because the museum contains wooden artifacts doesn’t mean it has to also be constructed from wood.

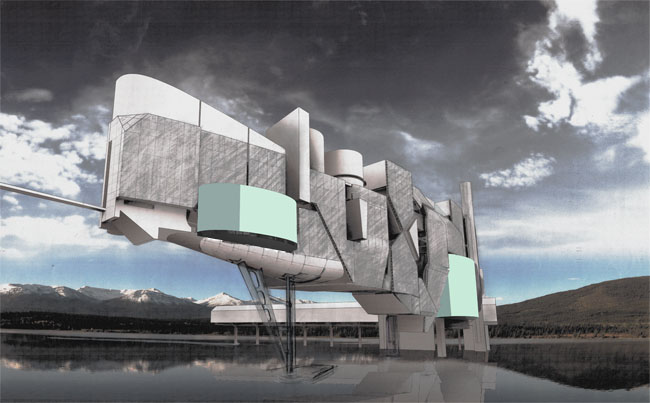

For the design iteration he presented at CriticalMass, he formed the building as two arms that extend from a single pivot point. One arm, which houses the exhibition spaces, features a series of shells with punctures and penetrations between them that are evocative of some woodworking techniques. Light is emitted in interesting ways – vertically, diagonally and horizontally – based on the type of breaks or fragments that occur between the shells.

The second arm houses the administrative and archival areas, as well as the old-growth tree, which he’s moved inside somehow.

This hand-rendered image by Brady Duncan shows his design of the Hardwood Tree Museum, in a view from the southwest. This is the final iteration of his project, which he showed in his final presentations on April 30.

Duncan said the other students’ work at CriticalMass clearly showed they’d had an additional semester to spend on their projects – mainly the research and background aspects, which they’d had more time to process and become comfortable with.

The process for work done in a single semester is inevitably compressed.

“We have a stronger, I guess, parallel working method, where our ideas and our drawings sort of have to manifest themselves simultaneously. And I think that’s a time thing more than anything else,” Duncan said. “Do they get as deep or as rich? I’m not sure.”

For this project, he did hand drawing, then scanned it. Using the computer, he did some editing and further processing, then printed it out again. He continued that cycle: draw, scan, digitally edit and print. “Then, you get these really rich, layered drawings,” he said. “It’s almost this compacted transparency.” One guest critic asked to keep one of those drawings.

“I think process is the most fascinating part,” he said. “It really shows the transparency of thinking behind what you’re doing – or not.”

Duncan is particularly glad that hand drawing was emphasized in his first year in the school. He said that direct connection is critical to his designs – and can’t be achieved when designing solely by computer. “It’s like the fewest layers of separation between what you’re thinking and what you’re producing,” he said of drawing by hand.

“That whole body-mind connective experience – from your eye to your brain to your hand – is the purest expression that you can generate ideas with. When you have to draw something, you have to be really conscious of it. But when you can just click and delete something, I think it becomes less intuitive. I think intuition is really important for students to develop and count on.”